Last summer, we published a blog about ‘off-rolling’ and pupils leaving their secondary school in years 10 and 11. Since then, we’ve updated our analysis and used the data in our inspections. This blog summarises what we’ve found.

Analysing schools with exceptional pupil movements in years 10 to 11

Last year, we looked at the movements of pupils between year 10 in January 2016 and year 11 in January 2017.

Over 19,000 pupils left a state-funded secondary school in the period. For about half of these pupils, we did not know their destination because they had not moved to another state-funded school. They may have moved to an independent school or to be home educated, but we could not be sure.

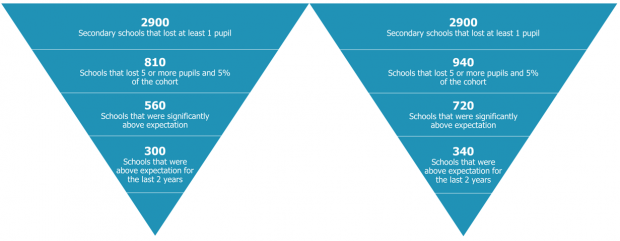

Using a statistical model, we identified around 300 schools that had exceptional levels of pupil movements when compared with schools with pupils with similar characteristics. There are often reasonable explanations for pupil movements, and the data is there to help our inspectors and regional directors to have conversations with schools, multi-academy trusts and local areas.

Updating this analysis and what we found

We’ve repeated this analysis by comparing school census data for January 2017 and January 2018. In that year, there were over 20,000 pupil movements between year 10 and 11. As in the previous year, we do not know the destination for about half of these pupils.

This year, our statistical model identified around 340 schools that had exceptional levels of pupil movements for two years running, compared with around 300 last year. The increase in the number of schools with exceptional pupil movement does not necessarily mean that off-rolling is increasing. There may be legitimate reasons for the increase in pupil movement. However, the increases do warrant further consideration.

On average, 13 pupils left each of these 340 schools between years 10 and 11: a critical stage in their education. Of the 20,000 pupils who left their school, 22% were in one of these 340 schools, despite these schools making up only 11% of all secondary schools.

Sixty per cent of the schools on the previous list of 300 schools are also in the new list of 340. Of those that dropped out, two thirds no longer meet the criteria of losing at least 5 pupils and 5% of their pupils, but many of these schools still lost some pupils.

A new analysis of pupil movements between years 7 and 11

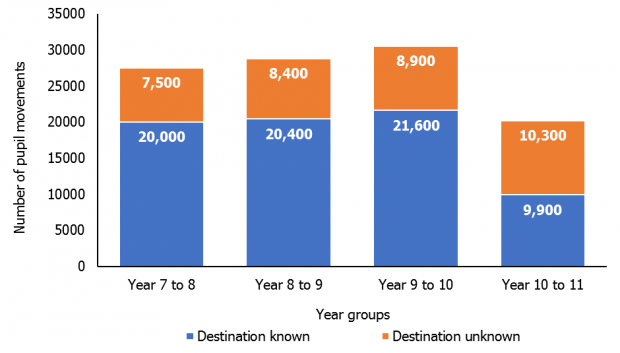

As well as pupil movements between years 10 and 11, this year we’ve also looked at movements between all year groups in secondary schools. Between January 2017 and January 2018, 107,000 pupils left their state-funded secondary school.

Pupil movements in younger year groups were higher than the 20,000 movements seen between years 10 and 11, though this is not in itself surprising as families like to avoid moving their children during the GCSE years if they can. Movements peaked between years 9 and 10, around the time pupils traditionally begin their GCSE courses.

Interestingly, the proportion of pupils whose destination is unknown (because they left the state-funded sector and we’re unable to track them with the data currently available) was lower for the younger age groups. For instance, 29% went to an unknown destination in year 9 to 10 versus 51% in year 10 to 11.

This may be a sign that in the younger age groups pupils may be moving because their family are leaving the area (and we can usually track these pupils to their next school), whereas more of the pupils who move in later school years are becoming home educated (and cannot be tracked). Unfortunately, we do not have data on pupils who become home educated. However, we do know that some of the older home-educated pupils (in the 14 to 16 age group) actually spend some of their time at further education providers, such as colleges.

How we use the data on pupil movements in our work

Over the past year or so, we’ve started to use the data on pupil movements in years 10 to 11 to:

- prioritise which schools to inspect

- ask schools about exceptional levels of pupil movements in school inspections

- ask local areas about movements of pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) as part of our local area SEND inspections

- talk to local authorities and multi-academy trusts about pupil movements in their area/in their schools, as part of our regular meetings.

Between 1 September 2018 and 30 June 2019, we inspected around 100 schools with high levels of pupil movement. Five published inspection reports from this period directly refer to ‘off-rolling’.

In many other cases, the data facilitated helpful discussions about why pupils left the school, such as:

- families leaving the area

- pupils moving to specialist school provision nearby (such as schools specialising in engineering)

- a lot of school choice in a small area, which may result in pupils moving school more often.

Inspectors also discussed what the school does to support pupils to either continue at the school or to find a place in other schools.

For further information on how we look at pupil movements and potential off-rolling on school inspections, please see this recent blog by Dan Owen HMI, Specialist Adviser for school inspection policy.

For further information or questions about the data on pupil movements, please contact Louise Butler at inspectioninsight@ofsted.gov.uk

2 comments

Comment by @TeacherToolkit posted on

Is Ofsted going to 'actually find out' where these 20,000 pupils move to? This is a huge safeguarding concern if we do not know...

And, who is taking a closer look at these 11 per cent of schools to find out what is going on and what reasons make it disproportionate? It's fine to offer the analysis, but where is the action plan?

Comment by External Relations posted on

Our data and analysis is used to plan and inform inspections. And where we have concerns about a particular school, we can inspect at any time. While we don’t have any enforcement powers, where we find evidence of off-rolling we will report it. It’s then for the authority responsible for the school—the governing body and, behind it, the local authority if it is a community school; or the academy trust board and, behind that, the Department for Education through the RSCs—to take action. Our analysis highlights that many of the pupils that leave their school don’t reappear in another state-funded school, and so we can’t tell from the data alone where they have gone to. However the individual schools should know.